Whether or not you want to hear it, some people will tell you all about the exact moment they fell in love or found Jesus. I have a moment like that. It’s the one that comes to mind whenever someone asks me how I became a writer. So bear with me. I need to tell this story.

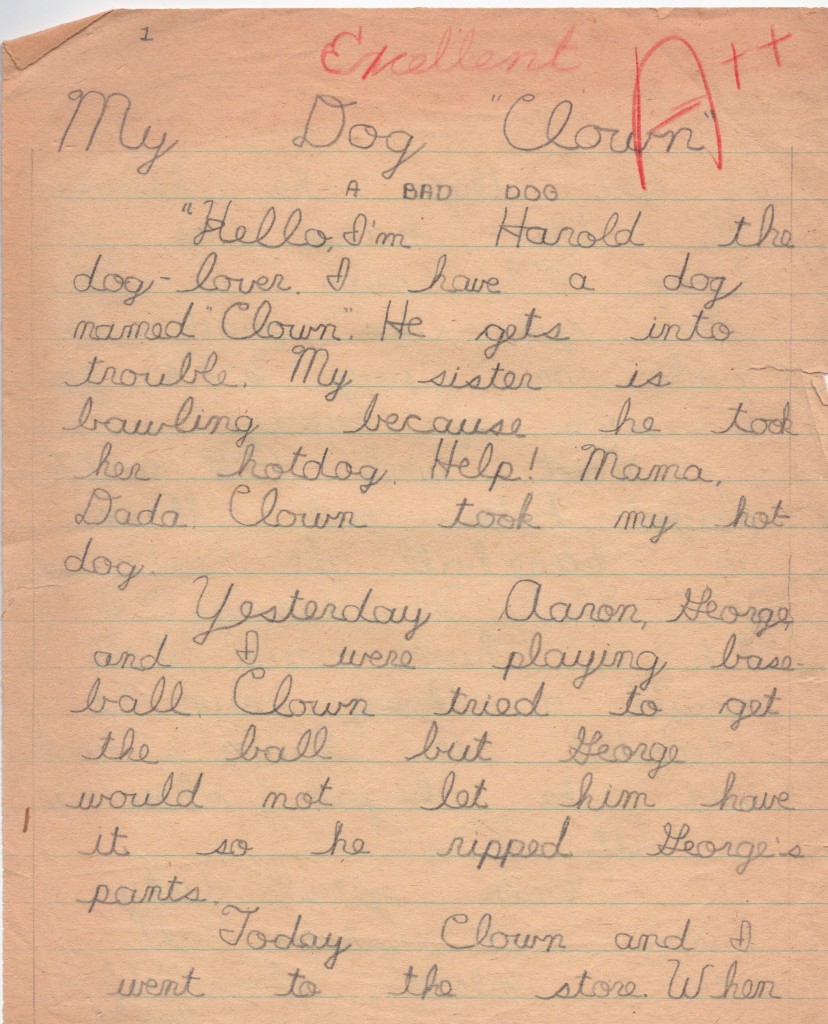

For about as long as I can remember I’ve been writing about something. My earliest school-time memories involve sitting at my desk during third grade composition time, oblivious to my surroundings, chronicling the adventures of various imaginary creatures that hid in the corners of my house. I relished those moments and even more so, the ones when my teacher returned my work with a bright red A++ on top.

Through the years, teachers and classmates at the small school in the small town where I lived lauded my literary ability. I never could catch a football and consistently turned the screwdriver the wrong direction in shop class (Righty tighty, lefty loosey, idiot!). But give me a pen and a pad of paper and I could put a string of words together to create a fantastic story.

I was introverted, certainly no class clown, but when I read my stories aloud I had everyone’s attention. “You’ll go far.” “Such an imagination.” “You have a real gift.” I basked in the compliments, yet a part of me still doubted. I attended a small school, after all, in a small town where people are generally kind to one another. I knew that the real test of my literary ability would be the opinions of strangers in faraway places.

At the age of 18, 1500 miles from home, I sat with 30 other college students in a required Freshman English composition class, clutching a folder filled with stories I had written during high school. I had told everyone back home that I would be majoring in English literature with an emphasis on creative writing, an obvious logical step on the way to becoming a Pulitzer Prize-winning author. I couldn’t wait to show the professor my folder full of stories, including the especially good not-yet-completed one for which I was contemplating a proper ending.

He looked every bit like I imagined a literature professor should look. He sported a slightly scruffy beard, and always wore a tweed hound’s-tooth jacket with patches on the elbows. He even brought an unlit pipe to class, the kind with the curve in the stem like Sherlock Holmes smoked.

He informed us that the first week’s assignment would involve composing two basic essays, which he would read in order to determine our level of skill and meet with us individually to discuss.

Two weeks later, I sat across the desk from him in a cramped office filled with a lingering aroma of cherry-scented pipe tobacco. He caressed his beard with one hand and flipped through a stack of essays with the other. “Ah yes, Eppley,” he said.

On my lap rested a folder with the especially good not-quite-completed story, which I planned to show him after our conversation. He procured from his pile my two essays, each covered with a massive amount of red ink and bearing a large “U” at the top.

“Not good at all,” he said.

He looked me in the eye and asked, “What’s your major?”

After an awkward pause, I said, “Physics.”

Physics was my least favorite subject in high school, but it was the only reply that came to mind in what was rapidly becoming one of the most painful moments in my young life.

“Fizz- ziks,” he repeated, with a hint of disdain. As though I had told him my major was underwater basket weaving. “That’s good. You won’t need to do a lot of writing then. Not all of us can write well.”

He was staring at me but I could not look him in the eyes, and in a room that small there were not many others places to look. I surveyed the pile of papers on his desk, not wanting to look at my own, and saw the word “Brilliant!” at the top of the essay belonging to Lisa, the attractive woman who sometimes sat in front of me. Apparently, she could write well.

I left the professor’s office, clutching the folder that contained my incomplete story and knowing that my deepest fear was true. My teachers and classmates from that faraway small town had been mistaken—I had no future as a writer. All their accolades meant nothing. In the real world, I was just another wannabe.

I returned to an empty dorm room. 1500 miles from my home, I was more alone than I had ever been. Overwhelmed by a suddenly insuperable sorrow, I fell into a deep sleep. I must have slept for 3 hours. When I awoke I knew how my almost completed story must end.

I pulled it from the folder and worked on it for the rest of the night, ignoring my roommate’s repeated invitations to accompany him on a beer-run. It was well after midnight when I finally completed the story.

I knew nobody would ever read it. I knew it probably sucked. I knew I would not become an English literature major or ever win the Pulitzer Prize. For the first time I could recall, I was not writing to receive accolades or bask in the glory of a bright red A++. I was writing because there was a story inside me and I could do nothing else until I put it down on paper.

Sometime during that painful night I had learned what it means to be a writer.

2 Responses to To Be A Writer